JENNIFER PRINTZ

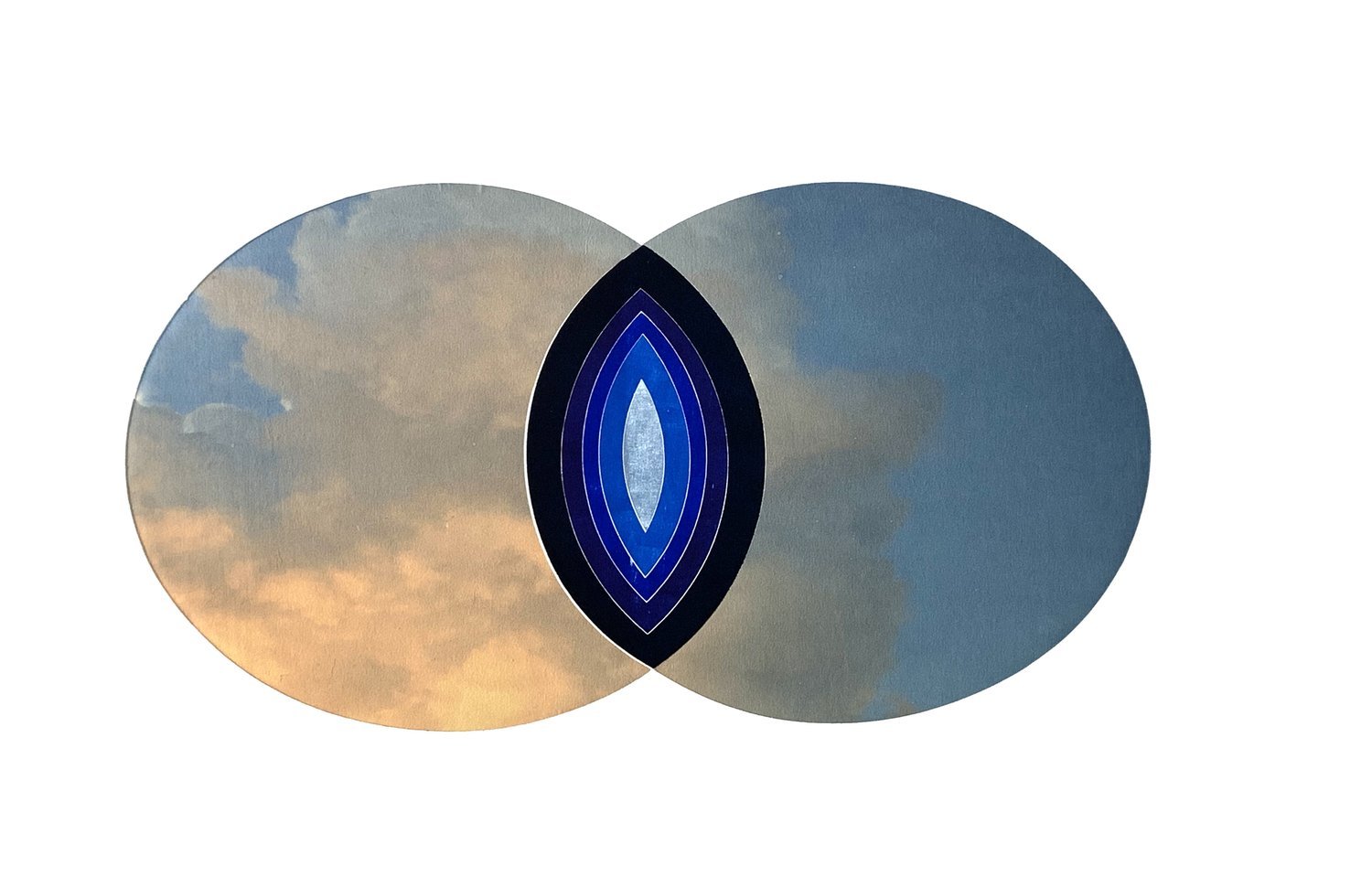

Existed Up To Now, 2022. Black carbon pigment, acrylic matte media on canvas with Epson Ultrachrome inks on silk, 55 x 117 inches

Combining drawing, photography, and textiles into poetic compositions that blur the distinction between abstraction and representation, Jennifer Printz explores ideas around atmosphere, presence, and time. Her multimedia pieces explore in-between moments that draw from daily observations and meditation and plumb the relationship between the known and unknown, the familiar and the new. Printz is also an educator who currently teaches and heads up the MFA program at Florida International University in Miami, Florida.

Kate Mothes: Do you view yourself as a multimedia artist or a photographer first? Or is there a way that you think about that distinction or even if it has changed as you've been working?

Jennifer Printz: You know, I don't consider myself a photographer. I should start there because photography is never the end product for me. I always do something more with it, outputting it onto paper then printing and drawing on top of it, or putting it onto fabric and making it into a sculpture, or incorporating via collage it into another piece. Since I have worked and studied with amazing final-product photographers I have an intimidation of using that label. I think I lean more into drawing. A big part of everything I do starts with drawing - drawing out ideas, putting pen or pencil to paper to come up with something to work out a composition.

However, my training and my formal education is in printmaking—both my bachelor's and master's degrees. The large amount of what I've taught over the years has been printmaking. I do think like a printmaker in that transference is a large part of my ideation. I also think about layering things together, thinking things through and then considering how to break it apart. As a creator printmaking is also a big part of who I am.

Is it mostly intuitive?

Certainly, I think it is because even if I plan something with a sketch, and I have a clear idea, I am very committed to letting the piece do what the piece needs, building in that space to be reflective or to respond to what's in front of me as a piece is developing.

Intuition and self-trust over the years has become a bigger part of my practice as I've grown as an artist. The textiles crept into my practice in because I grew up in the southeast of the States, and both of my grandmothers and much of my extended family, particularly my great-aunts were sewing in some way. My earliest memories of being taught to make something was first how to sew paper together, then how to do basic fabric sewing from my great aunts and my grandmother. But as I pursued my education, I left what I had learned about sewing to the side thinking that's completely different than a studio practice. And then at some point it was like, well, why? Why stay bifurcated? And so I've over time let it kind of seep more and more into my practice.

Lifetimes Alone, 2021. Relief print with chine colle (Epson Ultrachrome inks on washi), 15 x 22 inches

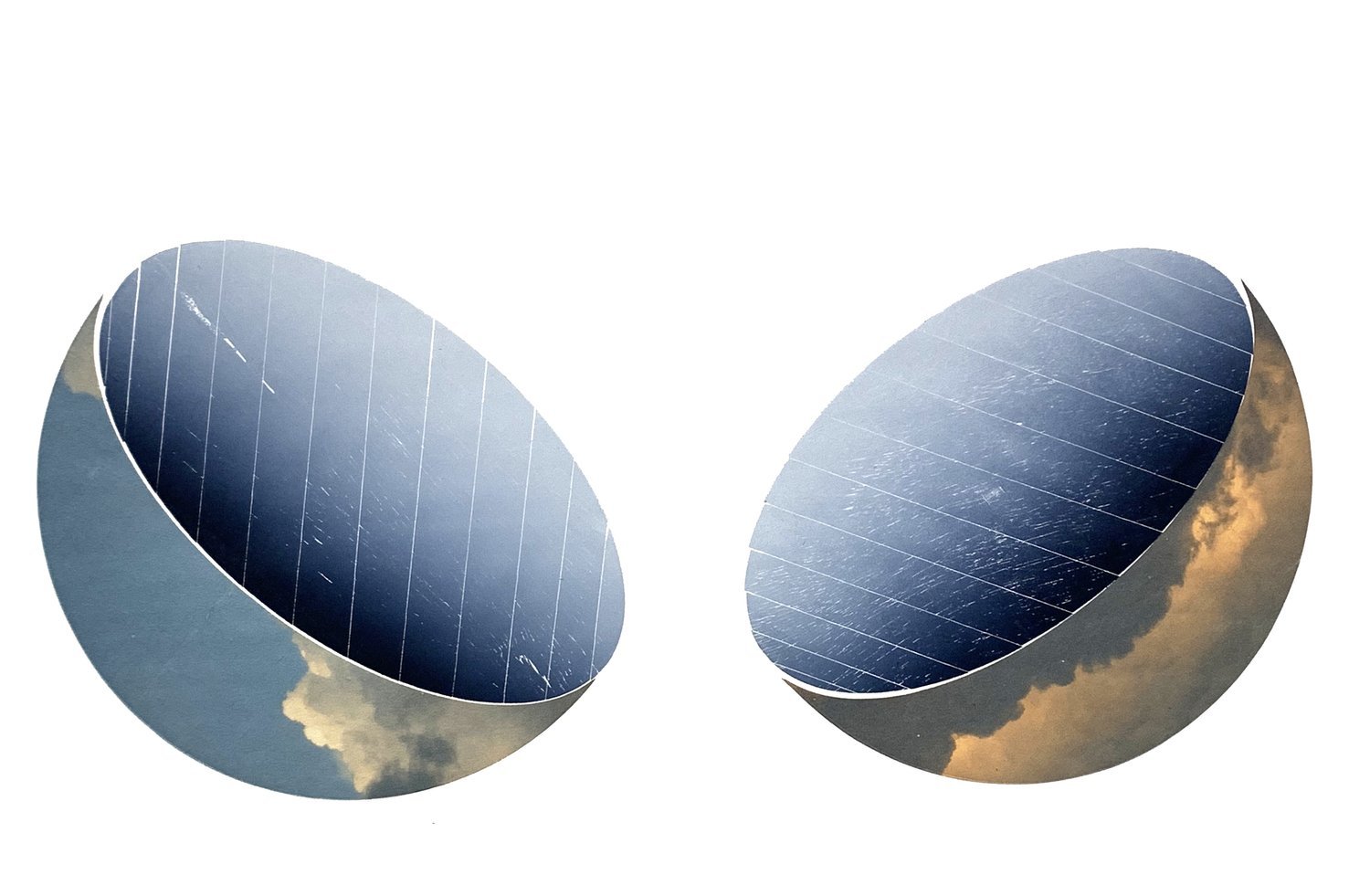

Truth and Time, 2022. Black carbon pigment, acrylic matte medium on canvas, and Epson Ultrachrome inks on silk, 55 x 156 inches (left: 55 x 39; right: 55 x 78 inches)

Textiles tend to sometimes be categorized as a craft with a capital C, just like art with a capital A, and photography with a capital P—they still are talked about in these silos, in a way, but then it's not necessarily helpful to think about them separately in terms of the processes. It's like, why can't it all just be together?

I think a lot of my exploration in the past few years has been based on that. Guided by questions like - why can't I put a photograph onto fabric? And then draw on top of that? Perhaps it is human nature to want to define things and create little boxes, but why do we? Why especially do we do that with a creative practice?

When you're starting a work, how do you begin? Do you begin with a photograph, or at this point, have you created lots of different pieces that you can pull from in order to get going?

I usually have numerous things going on at a time and part of that—just like a lot of artists—is that sometimes I have to stop on something; it needs to dry, it needs to rest, or sometimes I just need a break from it. So having multiple things going allows me to do that and it also allows for cross fertilization.

At this point, I have a huge library if you will, of photographs. And in fact, my time in Scotland this summer—then I spent a month in Austria—I was photographing every day, especially in Austria. I was climbing to the top of the Mönchsberg mountain in Salzburg and photographing two to three times a day as I walked a two-mile loop around the top of the mountain. I have that library, and sometimes I'll start with an image and then go from there. Sometimes I have an idea and then find what image fits, so there's no one clear path for me. Sometimes the idea just comes.

Right now, I'm working on a commission piece, and that puts my work in a different parameter. She likes this type of work, but she needs this, so how do I solve that problem? It totally depends on where I'm at. But I do think that when I'm starting a new project, there's always an underlying question or idea that I'm playing around with that guides me.

Chuck Close has this great quote, “Inspiration is for amateurs—the rest of us just show up and get to work.” And then he goes on to talk about the power of asking good questions of ourselves, and I think that's really important. What kinds of questions can I ask? Whether it's like: How can I measure the sky? What kind of patterns exist in nature that I can play from? Or what can I do with these hundreds of videos that I've taken over the summer? I've never done anything with video, but what can I do with these videos I just made?

Rising Up, 2022. Etching with chine colle (Epson Ultrachrome inks on washi paper), 30 x 22 inches

Speaking of residencies and thinking about questions that you're asking yourself, when you embark on a residency, do you position yourself with that question or give yourself a mission before you go, or when you're there, do you just let that question find you?

It totally depends. I have gone into residencies where I have an exhibition coming up soon afterwards, and I am totally on a mission to get the work done for that.

This summer, it was kind of an interesting time because I just finished several big projects and put so much energy into finishing them that I didn't have the time to create that mission before leaving for my residencies. It became more about just being open to having some fun creating. I made sure I had enough tools to work with, but thought more about what kind of research or materials I could gather that could take me on to the next place? Because living in Miami, I don't have the opportunity to climb mountains or to deal with this very pristine atmosphere. I mean, the sky is amazing here, but there are different atmospheric qualities among Miami, Scotland, and Salzburg, Austria. I was just allowing myself to take that all in so that then it moves me to the next projects that are coming up.

You do realize when you're traveling that the quality of the light is so different, the air is different, it smells different. All of those things must—the more time you spend and move around—trickle down into how you're just feeling about the work as you're making it. The sky tends to be a motif that you commonly use in the work. It's a very universal motif in a way, and I wondered if that was one reason behind it, something that pulls everything together?

It happened very organically as my life moved me around the United States. I lived in Los Angeles for about 10 years. Then I moved to the Blue Ridge Mountains in Southwest Virginia. The atmospheric quality from the smog-filled sky of Los Angeles to living in this valley in between mountains was huge! Virginia had these great, huge billowy clouds without the pollution of Southern California. I started taking photographs at first, just with my iPhone, without much thought other than appreciating and being engrossing in a moment of awe – of oh my God, the sky is beautiful! Sometimes literally pulling over in the car to take a photo of it. And then I hit critical mass in that way that sometimes artists do.

I've done this at different times in my practice where I accumulated materials or information and then suddenly started thinking, what can I do with this? This time it started with a residency in Valletta, Malta. I had been working with patterns and I thought I’d start playing with drawing patterns on these photographs of the sky. More questions started arising around things like: What's the sky? Why do we have to have a sky? What holds clouds in the sky?

That delved me into this deeper and deeper research about the sky as a metaphor. It seems like every culture on the planet has some sort of myth cycle that deals with the sky. There is this reality that if it wasn't for that 10-mile swath of gasses over our head, none of us would be living here on the planet. It is very universal, and my work reflects on that. It reflects on my interest in the environment and different qualities of the environment. And since my work pushes into the abstract, it's also kind of a nice entry point for a lot of people to start there and then to get more involved in the piece and what's happening within the work.

Integral Parts of the Oldest Riddle, 2022. Black carbon pigment and acrylic matte media on canvas with Epson Ultrachrome inks on silk, 60 x 163 inches (left: 60 x 45; right: 60 x 118 inches)

It’s a very simple but loaded question: Do you view them as landscapes? What's that relationship like between the sky and the ground?

The ground has been something that I intentionally have been, up to this point, leaving out. (And that could change!) I started thinking about the idea of landscape because for some time, other people have been putting that label on me, and I wasn't quite comfortable with it. For most of us, when we think of landscape, we think of paintings from the Hudson River School or art of that sort. That's definitely not me. Doing research and reading Tyler Green, who does the Modern Art Notes Podcast great book on Emerson and how Emerson's use of language and writing impacted landscape and our understanding of landscape has made me change my mind.

If you look at the word “landscape,” Emerson brings it into use in the 1800s, and he's looking at it not as “wilderness”—which is raw nature—but rather another kind of, as Tyler Green would say, interstitial place where both nature and the impact of humanity, combine to become a constructed space. If I work off that definition, then that's exactly what a lot of my work is about, right? It's about an organic photograph and then the overlay of my artistic hand on top of it—my construct. Or even in the most recent works, the contrast of the fluidity of the fabric and the photograph printed on it, up against a very strong geometric pattern. Within that perspective of the historical aspects of the word, I think it certainly fits, but it took that bit of research for me to feel comfortable using it.

That's a really good point that you make about the kind of mash-up, so to speak, of the built environment—the things that we've put into it—and nature, which parallels what you're putting into the work as you're making it.

Right, landscape is a construct. A great example I can think of is that in Scotland this summer, the residency director took us on a hike one day and we ran into rhododendrons, which I assumed were part of the wilderness. That made sense to me because, I found out later one of the two places in the world that they grow wild are Southeast Asia and then where I grew up in the mountains of East Tennessee and Western North Carolina. The director explained that in Scotland whenever you see rhododendrons, they are a sign that this location is a place where a noble or person of wealth had their home because they would have imported and planted these plants there. Just depending on your filter and your knowledge; something could be seen as wilderness, but then once you know you can see the construct – the impact of human intervention. This plant is not supposed to be here.

I do see a really interesting parallel between your built, geometric contribution onto this very uncontrollable natural atmosphere that everybody is just a part of. Then there’s the contrast of the idea of the ground and even the “ground” being like the ground of the paper or the surface that you're working on—even just semantically it’s interesting to think about.

Yeah, and you know, that's also one of the other things I think about is time, right? Because the way that I do photography, it's just that one, quick moment, but when I'm drawing or printing or constructing on top of that, then that totally changes. It's laying a different time sequence into it.

Through the Curtain of Yesterdays, 2021. Graphite, Epson Ultrachrome inks on paper, 22 x 15 inches

Do you tinker in the studio and come up with experiments here or there, or do you prefer to look at things as if approaching a whole new body or series of works all at once?

I tend to be pretty serial. I've always kind of been that way; if I'm going to explore this once, well, what happens if I explore it ten more times? It's worth doing once; if I do it two times, is it going to get better? Am I going to learn more? The way that I tend to go about things is working through multiples, which gives me the ability to edit, and gives me the ability to learn from the first to the third and so on.

Have you been experimenting with scale? It makes sense to be working on a slightly smaller scale with photography and drawing, but you’ve moved into sculpture as well. Is that something you've been moving toward?

When you're starting to deal with fabric, it's the lack of the rigid body with most of the fabrics that I use—the body is light, it can drape. That was an easy move, so then it's like, okay, what can I do with this? How can we impact a space by literally printing on this fabric and letting the sky fall with gravity onto the floor?

I received a commission to create new works for a medical center for a wall space that was 180 linear feet. I only had six months, which really isn't a lot of time. That was a point where I had to radically rework and jump up in scale. It was a good change, having a challenge to get out of my comfort zone. I think it's always good. And then for some of the projects that are coming up, I'm thinking about how to move more into environment—how to impact a space and create an experiential situation.

That’s a big technical question that comes up: if you've got a 180-foot wall, can you even use the same materials that you would use on other pieces? In a public space, is something going to get rubbed away? How does this initial thought translate into a different material and still get this idea across?

Public art is always a wonderful challenge. In this case I knew people would go by and due to the nature of this long corridor may touch the work. I ended up using water soluble graphite, but then instead of using water, I used acrylic media, so it was durable. I just had to build that into the work knowing that that could happen which is not typically a consideration in my work. Sometimes we have to think differently once we're outside of the typical white cube.

And even yesterday, I spent a lot of time completing a public art application where it was thinking of taking those patterns and sewing them in opaque and transparent fabrics that could be hung. They would act like stained glass where the sunlight would filter through, and the patterns would extend and change on the ground below. We'll see if that comes through or not, but even just starting to think about it, I was getting excited.

Delicate Crest of The Present Moment ii, 2021. Relief print with chine collé (Epson Ultrachrome inks on washi), 15 x 22 inches

The word “harmonious” came to mind when I look at your work. There are points and shapes that align—they hover—with the clouds kind of interspersed in there as well. There's definitely an impression of a sort of tension, of things not quite being complete; there’s movement implied in a lot of those works. I’m interested from the standpoint of your process or the act of drawing, is that meditative aspect something that you kind of view as part of the overall process?

125%! I recently was upgraded in my position, so I'm now director of an MFA program. That meant I had a lot less time in the studio in the fall as I was getting used to the new job. I noticed I wasn’t the same person! I try to be consistent with a daily seated meditation practice. But being in the studio, it is my meditation in so many ways. So that impetus has always—once I started thinking about mindfulness and meditation—been behind the work.

One of the ways I think about the artist's hand is about the transference of energy. I mean, we typically think about the artist's hand, about being aware about how they make the stroke or whatever physical qualities the stroke has. I think of it as coming through via how I'm touching and engaging with the work over and over, whether I'm stitching by hand or making marks or rubbing. In each case my visceral energies are going into the work. If I'm doing it as part of my meditation process, then I hope that ultimately those energies come through.

What are you working on now, and are you in the middle of any big projects or thinking about anything in particular that’s propelling you forward at the moment?

I’m at that point of starting to gear up. Right now, there is some studio cleanup, reorganization, and preparation. There are three things that are on the plate right now:

One is that I'm participating in a virtual residency with the Brehm Center at Fuller Seminary out of Pasadena and it's project-based. My goal is to create an installation that literally impacts the space to make it into this hopeful, meditative space. I'm kind of thinking about the Rothko Chapel and how, in my way, I would go about doing that within a particular space here in Miami. I'm excited about that, but that's just really at the very, very beginning.

I have a new series of woodcut prints that I will be working on. The wood has already been laser cut, and I'm going to abrade the wood to pull up the grain and print it. Those are all based on magnetic patterns within the atmosphere, and the sciences. They'll have that quality of basic repeating patterns, but they are very specifically grounded in science.

And then the last thing is that I'm thinking about drawing, the legacy of the mark, and my energies, if you will. I'm thinking deeply about a series of drawings where there would be so many marks that the paper itself would start to be damaged or start to disintegrate or destroy itself in some areas, so that visceral quality really comes through.

See more from Jennifer Printz:

Printmaking • Jennifer Printz • US Artists • Public art • Contemporary drawing

Originally from Northeast Wisconsin, Kate Mothes is an independent contemporary art writer and organizer based in Edinburgh, Scotland.