ELSIE KAGAN

New York-based artist Elsie Kagan hones a practice rooted in representative painting and its legacy in art and architectural history. Exploring the relationships between color, shape, and material, she has recently been interested in the language of the early Renaissance, especially “sculptures, friezes, and architectural maquettes—objects born in the wave of cultural rebirth after the devastation of a plague,” she explains. During a year of global travel with her family to participate in numerous residencies, she began to investigate the histories and problems of museums, narrative, and display. In 2019, Kagan also founded Interlude Artist Residency in Upstate New York, a program emphasizing accessibility for artist parents.

Kate Mothes: When did you begin painting? What attracted you to that medium?

Elsie Kagan: I was an only child, and had a lot of time by myself. From a young age I've been drawn to many forms of creative expression, from music to dance (my mother was a choreographer). But my sensitivity and interest in color took priority from a young age. I remember being fascinated with the interaction of different colors from my tiered 64 color Crayola set at 3 or 4. When I was 9, we moved to the Netherlands for a year. That's when I had my first encounter with real painting, at the Mauritshuis in the Hague, seeing Vermeers and Frans Hals, and those little Rembrandts. They just grabbed me, and still are some of my favorite paintings.

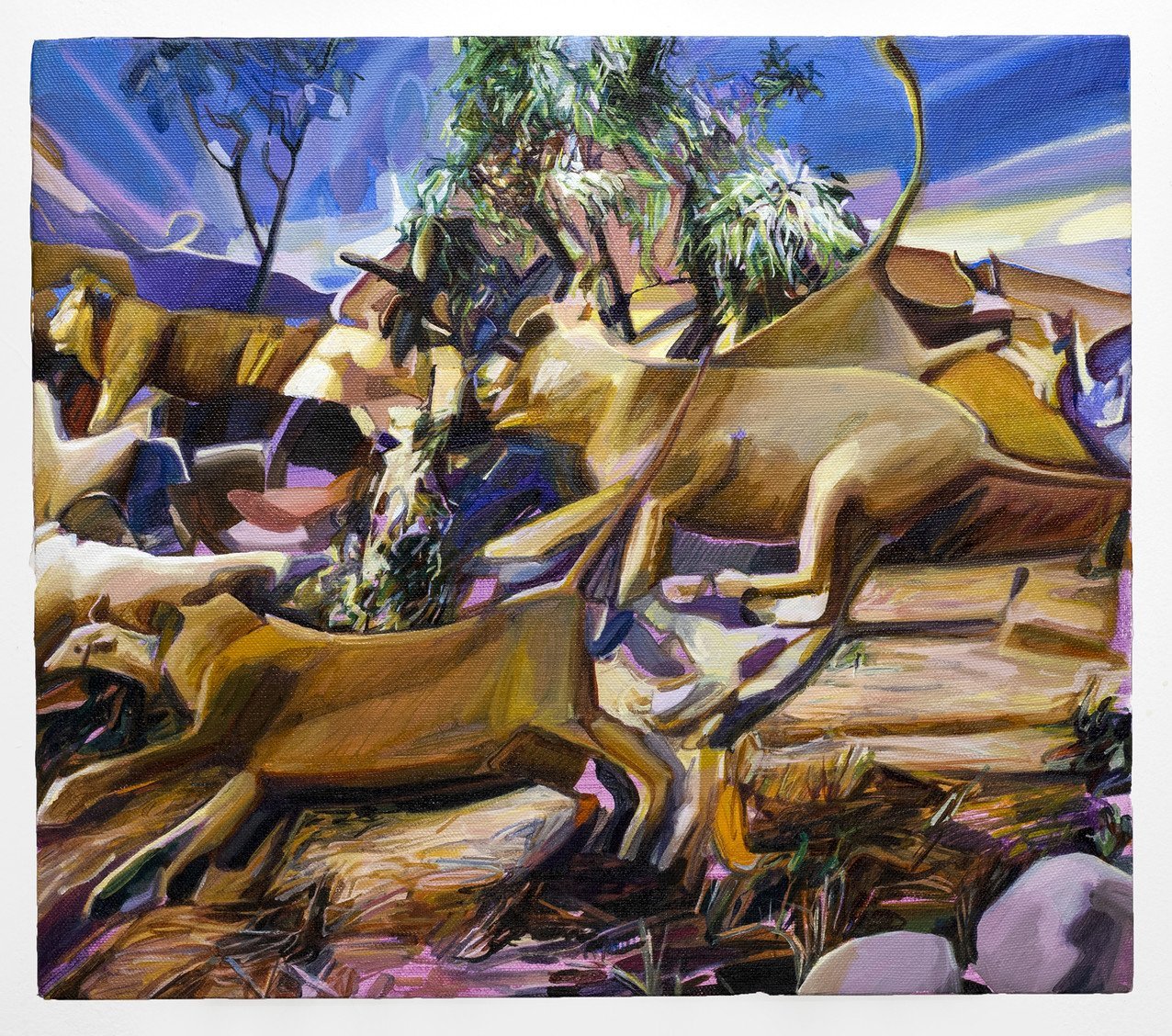

messengers and promises, 2022. Gouache and oil on canvas, 14 x 16 inches

Recently your paintings have focused on dynamic scenes of animals, sometimes in herds. What have you been thinking about or researching in terms of subject matter in the past couple of years, and has that changed or shifted from work you were making earlier?

My husband and I spent last year traveling with our three children. We spent time in Europe, Central America, the Caribbean, and 5 months in Kenya. I found the landscape in Kenya particularly astonishing, encountering animals and unmediated habitats that I had experienced otherwise only on screens or in zoos. Through the year, we also took our kids to many museums, which often employ dioramas as tools to engage audiences in an immersive way with the wonders of places and ecosystems on the globe, whether current or historic, anthropological, or wild. It was a long time dream, a now-or-never moment where there was a pause for my husband between jobs, so he could take the time off. We spent some time saving, and the kids were just old enough that they could handle it, but not too old that they would hate to be with us all the time!

I started to sketch and work from the diorama displays while we were abroad. The contrast between my experiences in the museum and my lived encounters deepened my interest in dioramas, as yet another subject matter through which I could explore themes in the studio. It is a seemingly endless source of exploration for me, both visually and conceptually. Like a medieval painting, a diorama is a carefully composed and contained story, presented to the viewer in a shallow field that describes a larger environment, offering several asynchronous events that can be read sequentially. Like a tapestry, the diorama is dense with information, made by craftspeople with specified skills. The diorama’s theater-like presentation, the way things are framed, and the interplay between two and three dimensions are also really rich territory for me to explore, as is its complicated relationship with the viewer.

Dioramas are didactic and problematic, and are biased and misleading, particularly when it comes to the fantasy of permanence and an unmediated perspective on the world, or a sense of unadulterated and 'pure' environments as we face catastrophic environmental and species collapse.

Since returning to the US, I've also become interested in diorama displays found in commercial environments, particularly in a chain of large outdoor and hunting equipment stores. These stores have numerous, baroque displays that celebrate who can be hunted with the guns available for purchase all around them.

bright topaz denizens, 2022. Gouache and oil on panel, 13 x 16 inches

What kind of research or preparation do you do when beginning a new piece? Do you bounce between working on a few at a time?

The research and preparation is various, but generally I spend some time on site with the types of objects or source material I'm interested in, and do some drawings. I also take photographs, and will sometimes make handmade collages with the imagery I've generated. I'm slowly incorporating some digital collage work into my practice but I'm hopelessly unskilled in that department. Mostly, I set out a palette to work with on a piece. Developing the color is probably the most pleasurable and meditative part of painting for me. I usually prepare a surface with a particular color that I want to respond to in the rest of the piece, which feels like a conflict to be resolved over the course of the painting. I prefer to have a couple of works going at one time, to lure me away from overworking or perseverating on a particular piece.

Left: the shortest day, 2020. Flashe on panel, 20 x 16 inches. Right: saper vivere, 2021. Pigmented plaster and flashe on panel, 20 x 16 inches

You work with tinted plaster—is this similar to fresco?—and also gauche and oil. What do you enjoy most about working with these mediums?

The tinted plaster is definitely a reference to fresco. I have long had in mind some longer term ideas about making fresco paintings, and hope to do a workshop with a fresco expert in Italy this summer. In the meantime, I asked another painter to teach me how to work with skimming plaster over panels and tinting it, which is essentially what Venetian plaster wall surfaces are. The plaster is layered very thinly in multiple steps over the surface and creates a wonderfully interesting and rich underlayer to my paintings.

One way I keep my practice engaging is to learn about different materials from others in the field. This can be a peer, in the example of the plaster, or someone who makes paint. I learned a lot from a particular paint maker named Robert Doak, who had a shop in Dumbo for decades. He taught me a lot about oil paint and pigment, about systems for my studio that keep the environment essentially solvent free and safer, and also about the possibilities of suspending pigment in vinyl instead of acrylic. Each material works differently and presents different possibilities for color, texture, and paint behavior in the work. I love having a continuing education in the materials I use.

Examples of Renaissance art and architecture like still life painting, religious iconography, and architecture play a role in your paintings—what draws you to that era of art history?

Painting is very indebted to and in conversation with its past. I'm always looking back to it as I wander through museums, looking for cues about how to communicate through the work and explore whatever themes are most relevant at the time. And I feel almost a yearning for a time when these modes of expression were more central and impactful within the cultures that produced them. To engage with this imagery and history for me is like a portal to that deeper sense of meaning.

just looking, 2022. Gouache and oil on panel, 12 x 18 inches

What prompted you to begin Interlude Residency in 2019?

Everyone's experience with parenthood is different. But for me, it was a kind of cleavage, and I still have a hard time managing my life as a mother with my life as an artist. There is also no doubt that it becomes a lot harder to find the time, energy, and resources to keep the wheels turning as a professional. During the early years, I did manage to attend residencies periodically. They felt like lifelines back to myself, and I would make more progress in a few weeks than I felt like I had the entire year. As I explored options for residencies that were open to caregivers, I realized that there really were none at all. Over the course of a few years, I devised a path to create a program myself. I founded the nonprofit program in 2019 and we began operating in earnest in 2021 after a year pause due to the pandemic.

Why do you feel it's important in particular to be inclusive to parents and families in the realm of residencies or development for artists?

It's a question of equity. The art world is still a very unforgiving place for many types of people, parents (especially mothers) among them. Artists need support throughout their entire careers. Parenthood appears right as many careers are beginning to take shape and artists are at their most capable and productive. Residencies are a piece of an artist's professional development, affording them dedicated time and support to develop work, networking opportunities, and are markers of excellence. Yet nearly all residencies expect an artist to appear unencumbered from any other responsibilities. That denies many worthy artists opportunities to thrive when they need it most, and continues a culture in the art world that is inequitable and exclusionary.

What do you enjoy most about facilitating the program?

If you give a parent the resources to focus on their work, it's glorious to see what happens. The residents are so grateful and excited to have the time and support to get in the studio, and they are amazingly creative and productive when given that support. The best thing by far is hearing from the artists about how meaningful the experience was for them.

you may ask yourself, 2022. Gouache and oil on panel, 12 x 18 inches

I imagined that you've probably been through a number of residency programs yourself before founding one. On your recent trip, or just in general, has there been a residency experience that you've personally participated in changed the course of your work or made you think about things differently?

I've found that there are moments in which the experience really amplifies and magnifies what might have happened without it. It's a distillation of studio life. There are out-of-time experiences where you feel like you're only an artist, your work is everything. Especially the residencies that I've done since I had kids, they're just the biggest gift I've ever had. They make me feel like I have a lifeline to something that is very frayed in the day-to-day.

Is there something that you look for in residencies?

I really like having encounters and forging new relationships when I'm there, because that's really where a residency can be useful beyond the moments in which you're making the work.

It can have an after-effect in your career when meeting with people, especially when you might be in a place in your life where that's just not happening naturally throughout your week or month. It makes you feel more alive and more legitimate as a creator to be in a world beyond one of feeling like you're kind of screaming in your studio and no one can hear.

There have been residencies in which there are meals that are prepared every day, and that is an extraordinary experience. It elevates the time that you have to work and makes it even more intense because you're not distracted by all the other stuff that you normally have to do. Those are things that I've been hoping to create as best I can, given our budgetary limitations at Interlude. We can't afford full catering, but we do provide two family-style dinners per week that are catered so that people know that that's coming and they can all sit down together and relax.

the blackbird is involved in what I know, 2022. Gouache and oil on panel, 13 x 16 inches

Has there been anything that really surprised you or happened unexpectedly once you were up and running?

Two things that I hoped would happen but wasn't sure would work: watching friendships grow between artists that are on site together, and how the kids can also bond with each other and have this really special, protected time. The other thing that surprises and delights me is how the children as well as the parents often experience a lot of creative growth on site. It is special for them to watch their parents in action in the studio, and it gives them space and license to become artists as well.

Do you think that running a residency program has an affect on your own work or the way you approach it?

The Interlude artists are all incredibly inspiring. I love learning about other parents and the ingenious and dogged ways that they are all nurturing their work and their kids at the same time. It gives me hope and encouragement.

What are you working on or thinking about right now in the studio?

One thing that I've been interested in right now is figuring out the scale of my work. When I started this current body of work, I was very constrained by what could fit in my duffel bag. I was making really small paintings, and they felt like these worlds unto themselves. That was really fun and interesting to do. Since I got home, I've been making more medium-sized paintings, which I realize now are kind of neither here nor there. I'm about to scale up in a major way. That feels exciting.

See more from Elsie Kagan:

Painting • Art History • Residency

Originally from Northeast Wisconsin, Kate Mothes is an independent contemporary art writer and organizer based in Edinburgh, Scotland.